Zoltán Berki, a stocky Hungarian man in his fifties, stuffs a few twigs into the iron stove in his kitchen, throws in a log or two, and then an old football boot.

“It burns, and we have to keep warm,” he said. In the northern city of Ózd, when temperatures reach freezing, other residents have also resorted to firing their ovens with polluting fuels like lignite coal, wood or illegal items like garbage to keep warm.

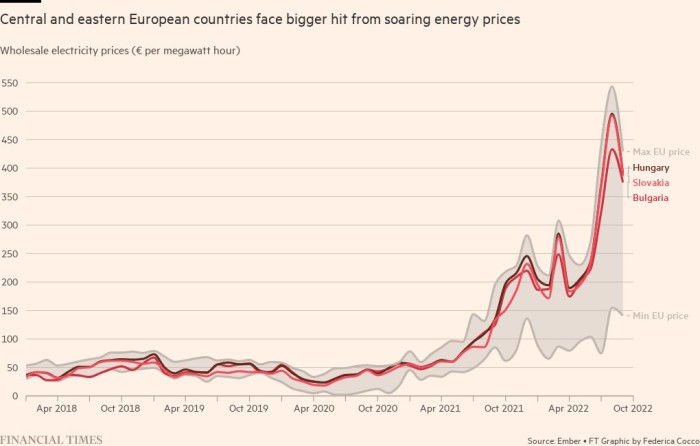

Getting through the winter has become a priority for millions of people in Eastern Europe who cannot afford higher gas and electricity prices triggered by the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Across the region, the cost of firewood has doubled since last year as households build up reserves. Rates of energy poverty, defined as the inability to afford sufficient heating supplies, are set to rise significantly in countries such as Hungary, Slovakia and Bulgaria, analysts say.

“If the prices of basic goods, mainly energy and food, increase, that pushes many people into poverty, and those who are already below the poverty line into extreme poverty,” said David Nemeth, a Hungarian economist. Belgian bank KBC Group.

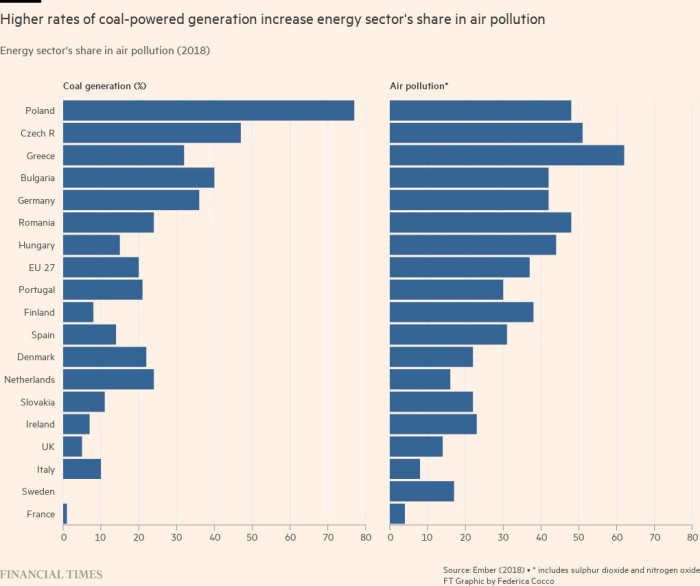

The increased use of toxic fuels also threatens to significantly increase emissions across the region.

“Years of development will go down the drain now. If their survival depends on it, people will burn anything,” said Zsuzsanna F Nagy, director of the Hungarian environmental group Green Connection Association.

Unable to find a job in Ózd, whose Soviet-era heavy industry has largely been shut down, Berki travels 150 km each way to work at an archaeological site in Budapest. But his monthly salary of around 500 euros leaves him little to buy firewood, which some stores now sell for more than 200 euros a cubic metre, about enough to heat a small house for a month.

Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orbán relaxed logging rules and ordered more mining for lignite, the high-sulfur lignite considered one of the dirtiest fossil fuels. The measures show how climate change has fallen off the agenda of many governments.

Lignite and wood were part of “the system we use to protect families” from the energy crisis, Orbán said last month. The lignite is once again powering the obsolete power plant in Mátrai, 75 km from Ózd, but it will also find its way into domestic furnaces. The area is a hive of activity as workers extract muddy lignite from nearby quarries several miles wide.

“Twice as many Hungarians die from air pollution as the French or the Dutch, relative to the size of the population,” said the Budapest-based Clean Air Action Group. “But the deaths are just the tip of the iceberg, as a hundred times more people get sick.”

Poland has scrapped quality standards for burning coal to reduce supply shortfalls after it accelerated an EU ban on Russian imports. Ruling party leader Jarosław Kaczyński last month told Poles to burn “everything except tires” to keep warm.

“People should not be put in the position of having to choose between heating their homes or harming their health because of pollution,” said Agnieszka Warso-Buchanan, a lawyer with the non-governmental organization ClientEarth in Poland, who predicts that the quality of air will collapse around the world. the region.

Poland is subsidizing the purchase of coal, which heats a third of homes. Other governments in the region are introducing emergency support measures, though mostly not on the scale of their Western counterparts.

“Support schemes are poorly established for the really poor,” said Dana Marekova, an environmentalist in Slovakia, where a fifth of households were defined as energy poor last year. The poorest Slovaks waste only small amounts of energy, she said, so they won’t benefit from a new law that subsidizes households that cut energy use by 15 percent.

Slovaks have extracted so much wood from the foothills of the Tatra Mountains that border Poland that the mayor of Nová Lesná, Peter Hritz, said his city was “going back 50 years” in methods of heating and pollution. “Suddenly, the smoke and smog don’t bother anyone,” he recently told Slovak media.

The winter heating crisis will be particularly painful in countries like Bulgaria, where two-thirds of rural households burn wood. Even before the war, 60 percent of low-income Bulgarians could not adequately heat their homes, according to Eurostat.

In Kosovo, one of the poorest countries in Europe, wood is burned in almost all rural households and in most urban households. A faltering power system, including regular blackouts, could help wood use double this year, according to Egzona Shala, executive director of the Pristina-based environmental group EcoZ. Illegal logging will not cover the fuel shortfall, she added.

More expensive and lower quality wood would drive a regional increase in illegal logging and the use of more harmful alternatives, Nagy said.

Lignite returns to power the Mátrai power plant in Hungary © Laszlo Balogh/FT

The smoke-shrouded city of Ózd © Laszlo Balogh/FT

For those who can afford more efficient heating units, supply is not keeping up with demand. The Hungarian furnace manufacturers’ association recently asked customers on Facebook to stop calling suppliers.

Back in Ózd, Berki burns toxic waste only at night so that the few police officers patrolling the area cannot see the black smoke. Many other homes burn waste under cover of darkness, blanketing local churches and a defunct smelter’s cooling tower with foul-smelling smoke.

But in Hungary’s largest segregated slum, near Miskolc, another former center of heavy industry and a short drive from Ózd, its 5,000 mostly Roma residents are bracing for harder times.

“I have a cubic meter of wood, which will be enough for a month, maybe,” said Gáspár Sipeki, like Berki a Hungarian gypsy. Sharing a hut with his son, Sipeki burns wood sparingly. When his stock runs out, he can buy more wood illegally through a clandestine deal deep in the Ózd Valley.

“What else am I going to do?” asked Sipeki, who works in a public works program. “I earn €150 a month, I can’t buy wood for €100.

Data and visual journalism by Federica Cocco